The day I arrived in New York to help deal with my father’s medical emergency, they were repairing the sewer pipe under my parents’ house.

The onslaught of noise was deafening as workers cut through an entire square of concrete then lowered themselves into the cavernous maze of underground pipes to search for the blockage. It took them two days to find the troubled spot, which had already plagued my parents for a week: no showers, no laundry, minimal dishwashing, and a directive to flush the toilet only when absolutely necessary. And after all that noise and digging, the blockage turned out to be not in the area where they’d dug at all. They found the problem in the sad little brick-enclosed square of dirt my parents call the “front yard”–under a rosebush that had already been reduced to small rootball and a few aspiring fronds.

The next day, when my father was officially referred to hospice and people rained all that “death is a passage” stuff on us, I thought about that sewer pipe–also a passage. And I also thought about the Dylan Thomas villanelle and its repeating haunting lines: Do not go gentle into that good night … Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

It isn’t that I want my father to fight against the reality of his dying. I feel grateful that he is not–and has never been–an angry or vengeful person. Even in his compromised state, while depressed about what is happening, he continues to exude kindness and express love and gratitude to those around him.

But I feel like raging. Not at the inevitability of my father’s death, but at the sadness of seeing him so frail and unable to do things for himself–the “dying” of my image of my 90+ year-old parents as timeless icons of longevity.

And I feel myself raging against the barely flickering “light” of my country. Yet this rage feels like a fruitless kick-the-floor-and-flail-my-arms temper tantrum. Pundits tell us to keep breathing and find joy. The sun is brilliant on the half-inch of freshly fallen snow today. But where is the balance between digging and doing what we can and totally abandoning ship, closing our doors and taking out whatever might constitute our modern-day “opium pipe” to lose ourselves in a stupor of disempowerment and apathy.

I’m forever grateful to Bishop Marianne Edgar Budde, who was able to channel her rage into a calm and quiet plea for mercy, focusing the whole time she spoke, toward whatever light might be left that’s still shining on who we could be–individually and collectively. And I’m wondering if that’s the kind of light that flashes before our eyes as we near the end of our lives in addition to reliving all of our life’s significant moments. I’m wondering what my father, an Emmy Award-winning journalist, is thinking as he sits hooked up to his oxygen machine with the New York Times spread on his lap, trying to stay awake long enough to get through more than a paragraph and make sense of all that’s happening around him.

Rage, rage, against the dying of the light.

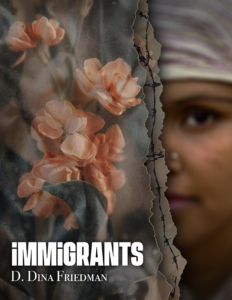

While we all have to accept death, as hard as it is, we mustn’t go gentle into this dark time, or accept the numerous attacks on our Constitution as the legitimate prerogative of a new leader. I feel grateful for the many in our community who are joining together and channeling their quiet rage into action. Death may be a lonely endeavor, but raging can be a community enterprise. I’m grateful to the many who are standing up to support immigrants, transgender people, the environment, and the many other important issues that are under attack.

In fact, what keeps me finding joy is knowing I have community–both to support me during this difficult personal time and to work together on keeping the light shining.

Subscribe at https://ddinafriedman.substack.com

Today my mother turns 90!

Today my mother turns 90!

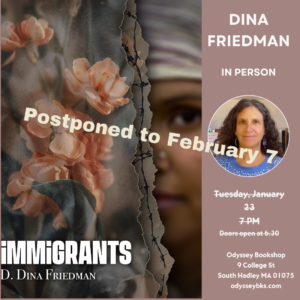

While I’m an admitted snowphobe when it comes to driving, I knew I’d likely be able to make it to the bookstore, which is only 5 minutes away from my house. But I also knew that others who were planning to come were driving much longer distances. I didn’t want to ask people to risk their safety. And I didn’t want to risk a low turnout. Even though I’d already bought the snacks and the ingredients for brownie-making, I decided it would be best to postpone.

While I’m an admitted snowphobe when it comes to driving, I knew I’d likely be able to make it to the bookstore, which is only 5 minutes away from my house. But I also knew that others who were planning to come were driving much longer distances. I didn’t want to ask people to risk their safety. And I didn’t want to risk a low turnout. Even though I’d already bought the snacks and the ingredients for brownie-making, I decided it would be best to postpone.

And the security people who searched bags in the extremely orderly array of lines were efficient and respectful as they handed people shrink-wrapped cooling towels, which seem to be a staple in the “wicked hot” Japanese summer–consistent temperatures in the 90s that feel even hotter due to the high humidity.

And the security people who searched bags in the extremely orderly array of lines were efficient and respectful as they handed people shrink-wrapped cooling towels, which seem to be a staple in the “wicked hot” Japanese summer–consistent temperatures in the 90s that feel even hotter due to the high humidity.

The day before, we had gone to the city gardens and seen a large ginkgo, one of only three trees that survived the bombing. We also went to the Peace Museum and barely made it through picture after picture of burnt bodies, story after story of people wracked with despair as they stumbled through rubbled streets, trying to find their loved ones. This was made even worse by the short political exhibit that followed, which emphasized how the U.S. felt it was “worth it” to drop this new weapon on already nearly defeated Japan if it would keep the Soviet Union from entering the war and sharing the spoils.

The day before, we had gone to the city gardens and seen a large ginkgo, one of only three trees that survived the bombing. We also went to the Peace Museum and barely made it through picture after picture of burnt bodies, story after story of people wracked with despair as they stumbled through rubbled streets, trying to find their loved ones. This was made even worse by the short political exhibit that followed, which emphasized how the U.S. felt it was “worth it” to drop this new weapon on already nearly defeated Japan if it would keep the Soviet Union from entering the war and sharing the spoils.