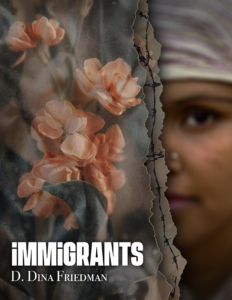

Last Thursday evening, as I was packing frantically to leave the next morning for a week-long trip for family events in Minneapolis, I got an email from my editor that my book, Immigrants, was finally live on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Apple, and Google Books. I still don’t have my author’s copies or any indication of what the final product (post proof corrections) looks like in print, so it felt a bit illusory to suddenly be published in the digital universe with no hard evidence.

Yet, finally here it was–available for any and all to read. And like–or not. And praise–or not.

While publishing is the goal for many writers, it’s also terrifying. Because even when it’s fiction–as this book is, your book is still a process of excavating the deepest things that matter to you and spilling them to the universe. And when you’re published, you no longer get to control who reads your work and what they’ll say about it. In fact, your goal is to get as many people as possible to buy your book in order to make your sales numbers look good.

This is why I always try to buy the books of writer friends I know, even if it might take a few months before I’ve have time to read them. And this year I’ve had some wonderful reads! Highlights were for adult fiction: Gene Luetkemeyer’s, My Year at the Good Bean Cafe, and Katheryn Holzman’s, Granted; for YA: Benjamin Roesch’s, Blowing My Mind Like a Summer Breeze, and Jeannine Atkins’ Hidden Powers; for memoir, Magdalena Gomez’s, Mi’ja and Ani Tuzman’s, Angels on the Clothesline; for creative non fiction, Anne and Christopher Ellinger’s Authentic Fulfillment; for poetry, Rich Michelson’s, Sleeping as Fast as I Can and Lindsay Rockwell’s Ghost Fires, and for a book on writing, Tzivia Gover’s Dreaming on the Page. (Note: While I mostly used Amazon hyperlinks, because that was easiest to search for, most of these books can also be ordered from a local bookstore, or you can contact the author or publisher if you prefer not to use Amazon.)

And if you have something complimentary to say–whether you know the author or not–it can be very helpful to leave a short review (1 to 2 sentences is generally sufficient). If you’re not an Amazon user, they sometimes won’t let you onto their platform, but Goodreads is also an option, as is simply spreading the word to friends you think might also like the book.

So, here’s my shameless way of pivoting to book marketing–a task I find as appealing is cleaning the toilet. If you feel so moved, I’d be honored if you buy a copy of Immigrants. And if you like it, please do leave a review. Or write to me and let me know what you thought. And while you’re at it, please check out some of the titles above.

No one expects the audience to have a great musical experience hearing them; yet, this teaches these children early on that they have a voice and what they are saying through their music matters enough for people to listen to them despite their flaws and inexperience. This is an important lesson not only for the children, but for everyone in our goal-oriented society. Our all-or-nothing approach when it comes to fame and accomplishment minimizes the personal sharing of one’s art on whatever “level” it’s at, and amplifies only those who reach the highest bars of success, causing many to quit and abandon their own artistic voices when they realize they’re never going to reach that level.

No one expects the audience to have a great musical experience hearing them; yet, this teaches these children early on that they have a voice and what they are saying through their music matters enough for people to listen to them despite their flaws and inexperience. This is an important lesson not only for the children, but for everyone in our goal-oriented society. Our all-or-nothing approach when it comes to fame and accomplishment minimizes the personal sharing of one’s art on whatever “level” it’s at, and amplifies only those who reach the highest bars of success, causing many to quit and abandon their own artistic voices when they realize they’re never going to reach that level.