I loved my recent trip to Japan, despite how many times I got lost.

The worst instance was when my husband and I were dragging heavy suitcases searching for our AirBnb. In the heat (95 feels like 106) we walked in circles for an hour, trying to follow directions that said: get out of the subway station (which exit?), walk under an underpass (there were at least three), turn left at the brown building (which one–nearly all the buildings were brown), then walk “a little while” and turn right at the big tree (of course, more than one tree). To the host’s credit, there were thumbnail photos of each step, but the views looked like everywhere else in the neighborhood.

Why didn’t I try Google Maps? I did, but the app didn’t recognize the transliterated address. It was only after we stopped a kind woman walking on the street that she was able to paste the Japanese address into her phone and locate the place instantly–right around the corner from where we were and only four minutes from the subway station. Apparently Google maps in Japan often doesn’t recognize transliterated addresses. And even when it does, the streets you’re supposed to turn on are written in Japanese characters, with vague instructions like “head Northeast.” If I were a Millennial, I might be better at holding the phone up and following the blue dot, as the younger members on our trip seemed to do effortlessly, but for every time I was able to navigate to a subway, restaurant, or sight-seeing venue, there were three more times I found myself suddenly going in the wrong direction (not to mention all the times I did, eventually, make it successfully to a targeted restaurant, only to find it closed when I got there).

But travel can be like that. As can writing. While it may not seem so at the time–especially in the heat with suitcases–there can be joy in the quest if you can recognize and accept that you may not get to your destination as easily as you might wish to.

All my novels have taken years to write because I kept veering off course. Even though I kept a consistent schedule, I didn’t know what wasn’t working until I’d spent several drafts on the wrong path–which was ultimately a lot more of a time sink than the day we took the bullet train in the wrong direction. It was only after I gave a few characters personality transplants, switched the points of view and totally revamped plot points several times that I felt confident that I was finally following the blue dot of the true story. Or was I? Even now, the back of my mind churns as the Google Maps arrow wobbles: What if I changed all the first person points of view to third person? Would that be stronger and more consistent? Do I have the energy and interest right now to take the plunge?

Some books on novel-writing advise people to spend time plotting out the story’s trajectory and developing the characters through extensive bios before writing a word. If you can do that, more power to you. I know I need to feel the thrust of the book by immersing myself in a situation before doing that kind of development work, so I usually wait until I have a draft or two done before tackling any of that. And I also know that even if I did try to plan everything in advance, I’d still find myself veering off my set map. This is a good thing. As Robert Frost said, No surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader.

It’s a lesson I wish I’d taken to heart at the time, taking cues from my husband, who oohed and aahed as he snapped photos of temples and pagodas that suddenly appeared among all the brown buildings, instead of fuming in frustration at that elusive blue dot.

To subscribe to this blog, sign up at ddinafriedman.substack.com

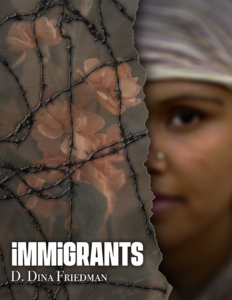

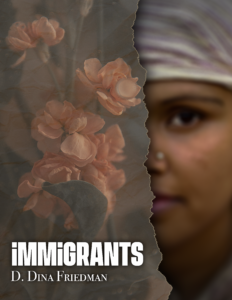

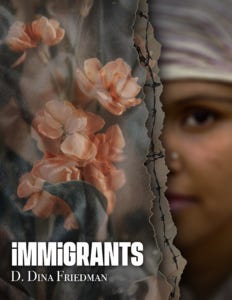

There’s an old adage… you can’t judge a book by its cover, meaning (according to the

There’s an old adage… you can’t judge a book by its cover, meaning (according to the  but I never liked the cover for my second book, Playing Dad’s Song.

but I never liked the cover for my second book, Playing Dad’s Song.  It wasn’t much consolation that the book with the cover I liked did way better than the book with the cover I didn’t like. I couldn’t help but wonder and wish that a stronger cover would have made a difference with this book’s performance in the market.

It wasn’t much consolation that the book with the cover I liked did way better than the book with the cover I didn’t like. I couldn’t help but wonder and wish that a stronger cover would have made a difference with this book’s performance in the market. Since poetry is tough to sell to people who don’t know you, I didn’t really think too much about market impacts, though I hoped the bright and engaging colors would evoke interest.

Since poetry is tough to sell to people who don’t know you, I didn’t really think too much about market impacts, though I hoped the bright and engaging colors would evoke interest.

And the security people who searched bags in the extremely orderly array of lines were efficient and respectful as they handed people shrink-wrapped cooling towels, which seem to be a staple in the “wicked hot” Japanese summer–consistent temperatures in the 90s that feel even hotter due to the high humidity.

And the security people who searched bags in the extremely orderly array of lines were efficient and respectful as they handed people shrink-wrapped cooling towels, which seem to be a staple in the “wicked hot” Japanese summer–consistent temperatures in the 90s that feel even hotter due to the high humidity.

The day before, we had gone to the city gardens and seen a large ginkgo, one of only three trees that survived the bombing. We also went to the Peace Museum and barely made it through picture after picture of burnt bodies, story after story of people wracked with despair as they stumbled through rubbled streets, trying to find their loved ones. This was made even worse by the short political exhibit that followed, which emphasized how the U.S. felt it was “worth it” to drop this new weapon on already nearly defeated Japan if it would keep the Soviet Union from entering the war and sharing the spoils.

The day before, we had gone to the city gardens and seen a large ginkgo, one of only three trees that survived the bombing. We also went to the Peace Museum and barely made it through picture after picture of burnt bodies, story after story of people wracked with despair as they stumbled through rubbled streets, trying to find their loved ones. This was made even worse by the short political exhibit that followed, which emphasized how the U.S. felt it was “worth it” to drop this new weapon on already nearly defeated Japan if it would keep the Soviet Union from entering the war and sharing the spoils.