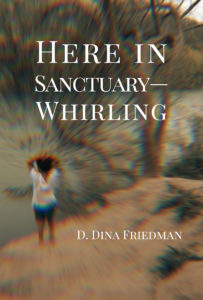

I got my first Amazon review of my new poetry book, Here in Sanctuary–Whirling, a few days ago. It was a 5-star rating, filled with wonderful phrases like “lyrical and evocative,” “alive and immersive,” “a sensory experience that is both enchanting and exhilarating.”

Only one problem: the reviewer depicted the book as “a mesmerizing fantasy novel …set against the backdrop of the mystical land of Sanctuary… At the heart of the novel is Whirling, a young girl with a deep connection to the elemental forces of wind and air.”

Ahem! This is a book of poems centered on my work in immigration justice and my witnessing trip to the border.

LOL!

Apparently, fake reviews–usually written by AI-bots–are a thing. Despite the many times I’ve had to go through hoops to post an Amazon review (I’m often told I hadn’t bought enough on Amazon recently to attain the privilege of posting on their site, or told to wait a few days while they verify my identity and authenticity) several writers in my network recounted similar experiences. “My poetry collection was called More Money Than God,” said Rich Michelson. “And one person gave me a one-star review, claiming I didn’t write enough about hedge funds.”

Still, I can’t help wondering–why are people doing this? Is this the new middle-school equivalent of making prank phone calls? At least then you had the pleasure of listening to someone’s reaction when you asked if their refrigerator was running and told them to catch it. I doubt whoever put up this review is hanging out in Cyberspace waiting for my reaction. (And there’s nowhere to put reactions or comments in Amazon reviews, anyway.)

And, if you’re going to write a fake review, why give a Bot the job? It’s much more fun to write these yourself. My family has spent many laugh-filled hours playing a game called Balderdash where you make up definitions to unusual words, write biographies for people you’ve never heard of, explain what various acronyms stand for, and write brief plot summaries for titles of obscure movies.

So, whoever you are, dear reviewer who goes by the name of Piper N., I dare you: next time, get together with a group of friends and write your own Balderdash. It’ll be a lot more fun–and even if you don’t sound as smooth as the AI-bot, you’ll get to stretch your creative muscles. But thanks for the five stars. And if I ever attempt a fantasy novel, I hope my main character, like “Whirling” will emerge “as a fierce and courageous protagonist who defies expectations and challenges the status quo.”–I’m all for that.

And perhaps, reviewers to come might call my poetry book, just as you called “Whirling’s” journey, “a testament to the power of resilience and determination in the face of adversity.” That would certainly make me feel like the poems in the book had been truly heard.

Any artists out there—I’d love to see what “Whirling” looks like.

One of my favorite suggestions (and a practice I already regularly engage in) is walking in nature. I learned this from my husky-shepherd, Lefty, who quickly made it clear that the key to keeping him calm was a long off-leash walk in the woods every day. I found this break so nourishing, I’ve continued the practice. Even though he’s been gone for 12 years, I make a point of walking daily in all kinds of weather. And when I need an extra nudge to get my tired or tense torso out the door, I channel the ghost of my four-legged personal trainer, remembering that even at the very end of his life, he’d battle his own demons of arthritis, fatigue and lethargy for the joy of being in the woods.

One of my favorite suggestions (and a practice I already regularly engage in) is walking in nature. I learned this from my husky-shepherd, Lefty, who quickly made it clear that the key to keeping him calm was a long off-leash walk in the woods every day. I found this break so nourishing, I’ve continued the practice. Even though he’s been gone for 12 years, I make a point of walking daily in all kinds of weather. And when I need an extra nudge to get my tired or tense torso out the door, I channel the ghost of my four-legged personal trainer, remembering that even at the very end of his life, he’d battle his own demons of arthritis, fatigue and lethargy for the joy of being in the woods.