I generally reserve Wednesdays for blogging, because the end of the week is busier, but today, I find myself wondering what to write about.

It’s likely a spread of the “writer’s block” that has permeated most of the rest of my writing life. It’s more like a silty fog than a blockade on the road. I can still delve into old poems/stories and revise them; I just haven’t been able to generate anything new that feels worth keeping.

So instead of writing, I’ve been using the time to pour through my lists of submission opportunities, dragging out poems and stories, reading them through, working on a few and then putting things together in batches to send on Submittable. This is not terrible. I’m still spending time with my words; I’m just not birthing new ones. But I’m missing the thrill of the generative process, saying something that feels important and urgent in the moment–something that matters.

I’m pretty sure the reason I’m feeling blocked is that I just don’t want to access the deep feelings lurking below the surface–my anger, fear and despair at all that’s happening in the world, tinted with the residue of grief from my father’s recent death. It’s not even that I’m feeling a need to write directly about these things, but to write anything of substance still requires a journey outside the carefully constructed contours of my world that I’ve struggled to hold front and center–even as I feel gratitude for having the reassurance of that world: the smiling greenery, the flowering trees, my friends and family, financial and food security.

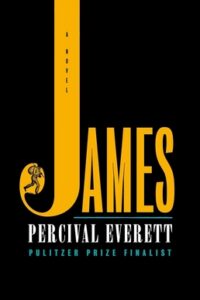

Today, in writing group, a quote from Percival Everett’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel James, a brilliant and poignant retelling of Huck Finn from the enslaved character Jim’s point of view:

Today, in writing group, a quote from Percival Everett’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel James, a brilliant and poignant retelling of Huck Finn from the enslaved character Jim’s point of view:

I did not look away. I wanted to feel the anger. I was befriending my anger, learning not only how to feel it, but perhaps how to use it.

And I realized that somehow I need to befriend my anger, my sadness, rather than keep it as a barely visible apparition on the other side of the fog. And then, simply brace myself, as the dam erupts, letting the rush of water and words spew forward.

Subscribe at https://ddinafriedman.substack.com