As we lit the Chanukah menorah on the first winter at our new house twenty-six years ago, my ten-year-old wanted to know if people could see the lights from the road. I think she was sensitive to ours being the only house in the neighborhood that wasn’t strung with Christmas lights and blinking Santas.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Let’s go see.”

We removed the curtain, placed the menorah in the front window, then bundled up and went outside. In the New England snow, our house, on top of a small hill next door to a farm with a Star of Bethlehem on the silo, looked gorgeous with the small menorah light twinkling at the window. I just wanted to stay out there forever under the amazing mass of stars.

We got in the car and drove down the hill, then turned so we could pass the house from below. “There it is!” I pointed. But to see our little menorah would clearly involve knowing that it was there, and a questionably dangerous maneuver of looking up at the house when you should be looking at the twisty road.

My children were not persuaded. “I want it to be like the star on the silo,” my six-year-old insisted as we pulled back into the driveway. “I want to see the menorah from far away.”

“It doesn’t matter. We can see it,” I tried to convince them. And then I had an idea. “Hey, let’s put menorahs on all sides of the house, and then we can walk around and see them, and the neighbors can see them, too!”

We lit three more menorahs, bundled back into our coats and boots, and crunched all the way around our snowy yard. One of the kids started to sing, and we all joined in: “Chanukah, oh Chanukah, come light the menorah/Let’s have a party, we’ll all dance the hora/every day for eight days, dreidels to spin/crispy little latkes, tasty and thin… When we got to the slope at the back of the house, the children stopped singing and flopped down dramatically, rolling all the way to the bottom of the hill. I felt my heart catch, but only until I heard them laughing.

This was so much fun that we did it again on the second night of Chanukah, and the third, and the 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, and 8th. Each time we got to the back of the house, the kids would engage in a dramatic fall and roll down the hill. Some nights were bitter cold with wind-chills below zero. Others were slick with ice. It didn’t matter. Going out to see the Chanukah lights became a test of our resolve and our fortitude. A tradition was born.

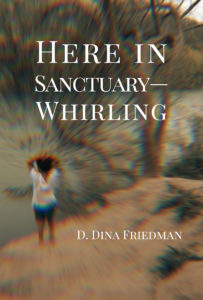

Photo: D. Dina Friedman

Photo: D. Dina Friedman

There’d be quiet as we waited. Sometimes we’d have to call a second time, or a third, but then we’d hear a rumble in the distance, as out of the dark he’d come bounding back, jumping on all of us over and over again as if giving an exuberant thank you for his special Chanukah present.

Lefty died in 2011, the same year my youngest left for college. My older child had already graduated and was living in New York City, so on the first night of Chanukah that year, the nest was truly empty. After Shel and I lit the Chanukah candles, I insisted on going out despite the fact that it was four degrees and the grounds were covered with a solid glaze of ice. We took ski poles and crept carefully down the ice-coated steps. At the front window, the small light of the menorah exuded warmth, the blanket of stars above us, magnificence, but I felt sad. I missed the kids, even though they were coming in a couple of days to celebrate Chanukah over the weekend. I missed the dog even more.

“We can walk the other way around the house,” Shel said. “It’s less steep.”

I knew the kids would have rebelled at any break in tradition, but I humored him and our old bones. We sang the song. At the end of the last line, I added “Lef–ty!” Like, “Play ball,” at the end of the Star Spangled Banner, the words just belonged there. I even looked across the field, half expecting to see him running toward us, but no Chanukah miracle.

When the kids came that weekend, they insisted on walking in the direction they’d always walked, and stopped, as usual, at the back of the house to dramatically roll down the hill. We sang the song, and of course, they too added, “Lef–ty!” to the last line—as we’ve done every year since then. At least one night every year, we still celebrate Chanukah with the children, their long-term partners, and now, a grandchild. But I still find myself looking across the field, waiting for that moment of rumbling and the speck of distant movement to get larger and clearer, our joyful dog coming back to us.

Originally published in Chicken Soup for the Soul, The Wonders of Christmas, 2018.

Subscribe to my blog at https://ddinafriedman.substack.com

We held up paper hearts and waved at them when they came out in their bright orange hats for 15-minute stints of exercise. Te amo (I love you) we shouted. Occasionally the children would take off their hats and wave them at us, though they were always reprimanded by the guards when they did.

We held up paper hearts and waved at them when they came out in their bright orange hats for 15-minute stints of exercise. Te amo (I love you) we shouted. Occasionally the children would take off their hats and wave them at us, though they were always reprimanded by the guards when they did.

Unfortunately, we were not in a position to engage in civil disobedience, so we had to settle for supporting the people on the bus with hearts and words of encouragement as they walked shackled into the plane’s belly and departed under the cover of the night.

Unfortunately, we were not in a position to engage in civil disobedience, so we had to settle for supporting the people on the bus with hearts and words of encouragement as they walked shackled into the plane’s belly and departed under the cover of the night. For most of my life, my writing and my activism were separate. But my writing has always come from my heart, and my heart is now intrinsically linked with these people who are far braver than I am. While I recognize that their stories ultimately belong to them and not to me, I’m glad they gave me permission to share these hard truths about their lives, which counter the rhetoric of even the supposedly liberal people in our government, because these stories need to be heard, loudly, by as many people as possible.

For most of my life, my writing and my activism were separate. But my writing has always come from my heart, and my heart is now intrinsically linked with these people who are far braver than I am. While I recognize that their stories ultimately belong to them and not to me, I’m glad they gave me permission to share these hard truths about their lives, which counter the rhetoric of even the supposedly liberal people in our government, because these stories need to be heard, loudly, by as many people as possible.