Yesterday, for the first time since my father died, I dived back into my writing.

Actually, it was my poetry critique group on Monday that started the waters churning. I had to come up with a poem, so I started looking through some old ones, and found one that reflected the grief I was feeling, even though I’d written the poem several months ago–after the election, but way before my father took a turn for the worse. Yet, the grief in the poem was so raw, my poetry group was surprised that it wasn’t a new poem. I guess grief has been in the air for a while, as the foundations of the country continue to rumble.

To tell the truth, I’d forgotten I’d even written this poem. I was simply pawing through my files of dribs and drabs, musings and snippets, trying to come up with something that felt like it had potential and held my interest enough to talk about. I got some good feedback–enough to bring the poem up a level or two. But more importantly, I got tacit permission to spend yesterday meandering through my piles of words, reordering, adding on, sloughing off, sewing together a few more poems for the “Send Out” file, piling up others to kiss goodbye before relegating them to the file marked “Inactive.” and leaving the vast majority in the file marked, “Poems to Work On,” but with the magical expectation that at least some of the changes I made might nudge them closer to send-out status soon.

Poet Molly Peacock, in a biography of Mary Delany, who invented the art of mixed-media collage in the 1700s, wrote, “Having a collection, taking it out, looking at it, reordering it, and putting it away is creative in itself. It doesn’t yield a product, like the results of an art, but stops time, as making art does.”

My style of writing poetry is somewhat like collage. I often seek to combine disparate images and make them add up to a whole. But more importantly, yesterday morning, for a few hours I stopped time as I took a few small steps away from my personal grief and the grief I’m feeling for our nation. Did I create art? That remains to be seen. Was the grief still there when I stepped back in? Absolutely, but I’m beginning to clear away the fallen branches and tangled vines and find a small path forward.

After my little writing vacation, I turned to some activism tasks I also hadn’t been able to do in the past few weeks: drafted a letter to the editor from our immigration justice group and wrote two call-to-action entries for Rogan’s List. It’s still hard not to get paralyzed by the enormity of it all, but taking time to put words together in a hopefully coherent manner made me feel empowered, rather than disheartened.

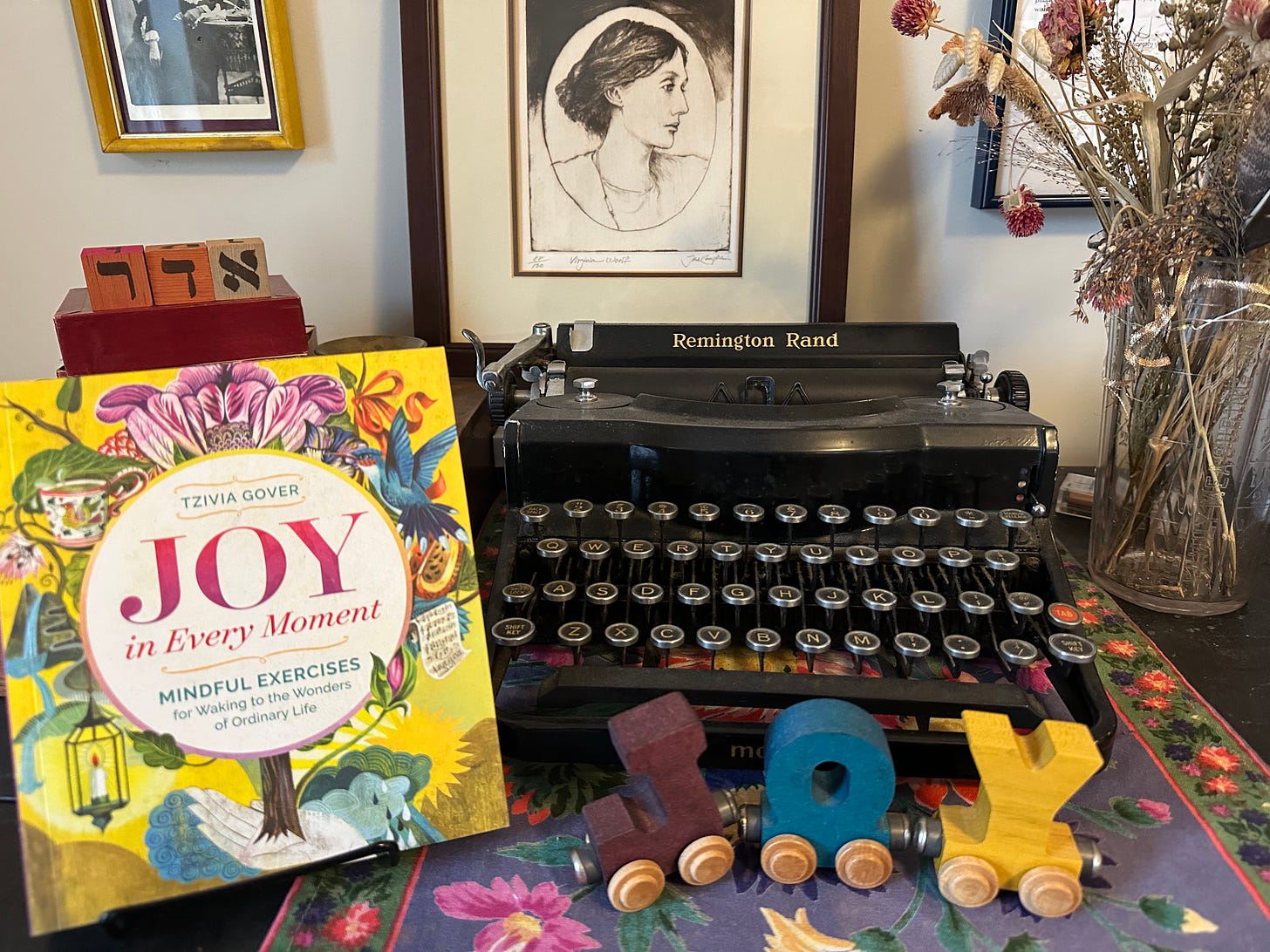

This morning, I’ve taken another step in returning to normalcy, writing with some of my favorite pals in the Forbes Library Zoom Group, where my friend and colleague, Tzivia Gover, with whom I’ve co-blogged a few times, introduced the quote above. Tzivia sent me this beautiful sympathy card featuring one of Mrs. Delany’s collages. I’m looking forward to reading The Paper Garden: Mrs. Delany Begins Her Life’s Work at 72.

This morning, I’ve taken another step in returning to normalcy, writing with some of my favorite pals in the Forbes Library Zoom Group, where my friend and colleague, Tzivia Gover, with whom I’ve co-blogged a few times, introduced the quote above. Tzivia sent me this beautiful sympathy card featuring one of Mrs. Delany’s collages. I’m looking forward to reading The Paper Garden: Mrs. Delany Begins Her Life’s Work at 72.

Subscribe at https://ddinafriedman.substack.com

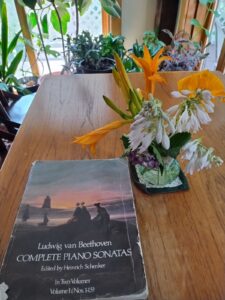

Oh well, I’ll tackle that issue later. First, I’ll have to think about the reframing. I’ll keep the current version, just in case, but in general, I like revision, which I think of as re-visiting, rather than correcting something that was previously wrong. I’ve recently discovered that in my piano life, as I re-visit pieces I struggled so hard with four years ago, like Beethoven’s Pathetique, I have a lot more facility in bringing them back. Frequent practicing has made my fingers stronger and more flexible, and I can focus less on the notes and more on the shadings of a piece, how I want to express it, which gets to the soul of the creative process–especially as I’ve learned to let go of the expectation that I’ll play every note and every rhythm perfectly and without bumps.

Oh well, I’ll tackle that issue later. First, I’ll have to think about the reframing. I’ll keep the current version, just in case, but in general, I like revision, which I think of as re-visiting, rather than correcting something that was previously wrong. I’ve recently discovered that in my piano life, as I re-visit pieces I struggled so hard with four years ago, like Beethoven’s Pathetique, I have a lot more facility in bringing them back. Frequent practicing has made my fingers stronger and more flexible, and I can focus less on the notes and more on the shadings of a piece, how I want to express it, which gets to the soul of the creative process–especially as I’ve learned to let go of the expectation that I’ll play every note and every rhythm perfectly and without bumps.