Every spring, as soon as I start gardening, my shoulder begins to ache, a dull pain that often spreads all the way down my arm. It’s not debilitating; it’s just annoying, but it’s pretty constant and I have to keep reminding myself not to overdo–set the timer and tackle the ubiquitous onion grass for no more than half an hour. Lately I’ve been feeling it most when I’m lifting heavy rocks to weigh down seed covers and cardboard mulch. And in the wee corners of my mind, I hear the niggling question of how much longer I’ll have the physical ability to keep on with this yearly seasonal ritual that brings me so much joy. Hopefully for a long time, I tell myself, deflecting with my usual optimism/denial reflex on any issue that relates to my own aging.

Photo: D. Dina Friedman

This morning I felt torn between gardening and writing group, since it’s going to get hot in the afternoon and I have a bunch of things to do then, but I chose the lure of writing group community, where someone made a random comment, “It has been a time and it’s not over.”

My friend was referring to events in her personal life, while also acknowledging that many people our age (50s and 60s with aging parents) are going through something similar. But I believe this heaviness is currently permeating among all ages as we read story after story of children starving and being indiscriminately killed in war zones, humans taken off the streets by masked men in military gear, and the myriad other ways our rights to shelter, health care, and food security are being dismantled.

I’ve encouraged people in our immigration justice advocacy network to join me in sharing some of the personal stories of immigrants who’ve been arrested, kidnapped or disappeared, knowing that reading about actual humans with lives and back story can get people in the gut in a way that vague policy statements or piles of statistics don’t. (Though one stat I will emphasize: very few of the people taken have a criminal history, unless you count trying to enter this country for a more economically secure life free from gang violence and death threats a crime. All this talk about murderers, drug dealers and rapists is a lie fabricated by the administration that’s also intended to get people right in the gut.)

However, my resolve to share these stories has gotten to the point where I can’t keep up with the flood of incidents coming into my inbox like weeds each day–high school students, families with young children, neighbors, friends…And to tell the truth, I don’t even want to read these upsetting stories any more. And if I, despite spending most of the last decade as an immigration justice activist, don’t want to read them, how can I expect others to?

Photo: D. Dina Friedman

Back at a demonstration on the border in 2020, we projected a sign. Don’t Look Away! Yet, there are some days that all I want to do is look away–curl up with the blessing of my meditation app that encourages me to simply cultivate a lens of neutrality and observation and be present in the moment.

How do we balance this appropriately mindful adage for self-care without forsaking our responsibility to our fellow humans? I keep thinking about Nazi Germany. Not the people who actively collaborated with Hitler, and not the people who risked their lives by hiding Jews in their barns and attics, but the people who may have quietly disapproved of what was going on, but did nothing and went about their lives as best they could.

Photo: D. Dina Friedman

I don’t want to be one of these people, and yet, I fear that’s what we’re all becoming. Not because we’re bad people. We’re just numb. Paralyzed by the heaviness of it all.

How do we hold onto the heavy and continue to take steps forward to address injustice, perhaps with the clarity and gentleness that mindfulness might bring? Somehow despite the pain, we need to keep lifting those heavy rocks.

Subscribe at https://ddinafriedman.substack.com

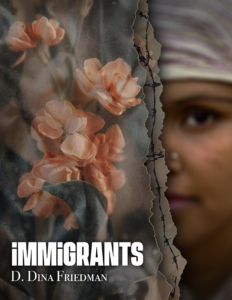

During this administration’s first term, when I wrote the stories in my collection

During this administration’s first term, when I wrote the stories in my collection

I’m personally very mixed on the “awards/contest” game for books because it seems like mostly a way of collecting a lot of exorbitant entry fees just to say your book won an award, but my publisher and I did submit to a couple of the more known ones. I was pleased to get a finalist designation (first runner up short-story and all category short-list) for the Eric Hoffer Awards, and a finalist designation in the short story category for the Independent Authors Network.

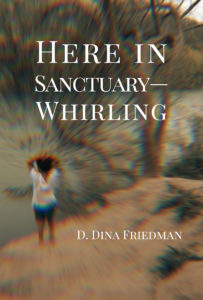

I’m personally very mixed on the “awards/contest” game for books because it seems like mostly a way of collecting a lot of exorbitant entry fees just to say your book won an award, but my publisher and I did submit to a couple of the more known ones. I was pleased to get a finalist designation (first runner up short-story and all category short-list) for the Eric Hoffer Awards, and a finalist designation in the short story category for the Independent Authors Network. It was a thrill to have my poetry book, Here in Sanctuary–Whirling, which drew heavily on my witnessing trips to the border and the children’s detention center in Homestead, FL, come out in early 2024. With the upcoming administration’s about to take over and put their extreme deportation plans in gear, this book feels even more relevant right now, and I’m continuing to look for ways to publicize it.

It was a thrill to have my poetry book, Here in Sanctuary–Whirling, which drew heavily on my witnessing trips to the border and the children’s detention center in Homestead, FL, come out in early 2024. With the upcoming administration’s about to take over and put their extreme deportation plans in gear, this book feels even more relevant right now, and I’m continuing to look for ways to publicize it.