After a week and a half of cooking nearly every day, I still have 7 beets, 11 carrots, one huge sweet potato and one huge daikon radish. And more food to come on Saturday!

In western Massachusetts, where I live, supporting the local economy is a huge value that transcends red/blue leanings. At the top of the list is buying from local farmers. In the summer, you can find a farmers market in one of the surrounding towns almost every day of the week. They are always packed with people willing to spend a premium for the privilege of fresh, local food and the knowledge that they’re contributing to their neighbors’ labors of love. I also purchase summer and winter farm shares from various CSA farms for both myself and my children and their families. This means that at this time of year I’m basing more of my diet than I’d like on parsnips, radishes, and beets, but it’s still worth it to know I’m eating in sync with the season and supporting my community.

A second value that many of us share is supporting local businesses. While it’s often easier and sometimes cheaper to shop on-line (and I fully recognize that there are many people with various health or financial challenges for whom that’s essential), I try whenever possible to patronize local stores, often setting a challenge to myself to locally source all my holiday shopping. And since books are one of my favorite gifts to give, I end up spending a lot of my holiday shopping time at local bookstores. We have so many good ones. My favorites are (in alphabetical order): Amherst Books, Booklinks, Book Moon, Broadside, and the Odyssey Bookshop.

Independent bookstores often have an on-line component, which means you can order most books also available on Amazon through their systems. The price might be a few dollars higher than the Amazon price, but to me, that’s no different than paying a local farmer a little bit more to assure that they can meet their bottom line and stay in business.

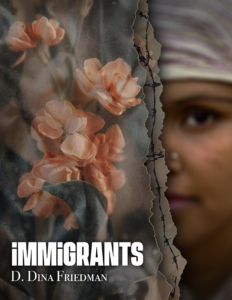

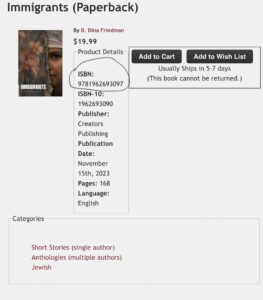

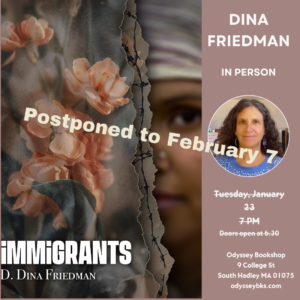

However, not all books can be obtained at local bookstores. Many smaller independent publishers encounter obstacles or simply don’t choose to go through the extra hassle of getting their books on the Ingram distribution platform that these independent bookstores use. I had to lobby hard with my publisher before they were able and willing to get the book on Ingram–under a different ISBN, just to make things confusing– and that didn’t happen until six weeks after the book was published. In the meantime, I was grateful to the bookstores who were willing to take copies of Immigrants on consignment in order to address the concerns of many of my friends who told me they’d love to buy my book, but only if they could get it at a local bookstore. And I’m especially grateful to the Odyssey Bookshop for hosting my book launch event, now re-scheduled for February 7.

and that didn’t happen until six weeks after the book was published. In the meantime, I was grateful to the bookstores who were willing to take copies of Immigrants on consignment in order to address the concerns of many of my friends who told me they’d love to buy my book, but only if they could get it at a local bookstore. And I’m especially grateful to the Odyssey Bookshop for hosting my book launch event, now re-scheduled for February 7.

And I’m grateful to the friends who bought the book to support me, just as I try to support local writers by buying their books–another way of giving back to the community. This week I ordered three books from people I know through writing: Dean Cycon’s Finding Home: (Hungary 1945); John Sheirer’s For Now, and Eileen Cleary’s Wild Pack of the Living. I’m looking forward to reading these books. And if I like them, I’ll make to write a brief review on Goodreads and Amazon (I buy just enough from Amazon to make sure they’ll accept me as a reviewer). That’s another easy way to support a local writer. You don’t have to sound brilliant–and I generally don’t. One-to-two sentences can make a big difference.

And even if you’re not a big reader, buy a book for someone you think would enjoy it. Or buy an EP from a local musician, or a small piece of art or craft item from a visual artist. Just as we need fresh produce to nourish our bodies, we need art in all its forms to nourish our spirits. And we need to let the local artists in our community know we care.

While I’m an admitted snowphobe when it comes to driving, I knew I’d likely be able to make it to the bookstore, which is only 5 minutes away from my house. But I also knew that others who were planning to come were driving much longer distances. I didn’t want to ask people to risk their safety. And I didn’t want to risk a low turnout. Even though I’d already bought the snacks and the ingredients for brownie-making, I decided it would be best to postpone.

While I’m an admitted snowphobe when it comes to driving, I knew I’d likely be able to make it to the bookstore, which is only 5 minutes away from my house. But I also knew that others who were planning to come were driving much longer distances. I didn’t want to ask people to risk their safety. And I didn’t want to risk a low turnout. Even though I’d already bought the snacks and the ingredients for brownie-making, I decided it would be best to postpone.

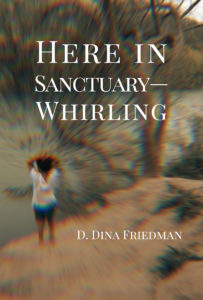

And as I was going full-steam ahead, a surprise snuck up on me. My poetry book Here in Sanctuary–Whirling was suddenly in its final stages of pre-publication. In fact, it’s scheduled to come out from

And as I was going full-steam ahead, a surprise snuck up on me. My poetry book Here in Sanctuary–Whirling was suddenly in its final stages of pre-publication. In fact, it’s scheduled to come out from  While I did what I knew I was supposed to do as a good book marketer: posting the link widely on social media and sending it around by email, there was a part of myself that just wanted to crawl into a dark place and hide from the rushing current of accolades. Can’t I just be humble? that small inner part of me whined. Why do I have to call so much attention to myself?

While I did what I knew I was supposed to do as a good book marketer: posting the link widely on social media and sending it around by email, there was a part of myself that just wanted to crawl into a dark place and hide from the rushing current of accolades. Can’t I just be humble? that small inner part of me whined. Why do I have to call so much attention to myself?