More than forty years ago, when my grandfather died, my father, who was sitting next to me at the funeral home, gestured to the person giving out the prayerbooks and said, “That man has a walk-on in my life.”

As usual, he was going for the one-liner, squeezing the humor out of a sad situation by taking a step back and focusing instead on a random absurdity.

Even now, at 93 and in the end stages of his life, as he drifts in and out of moments of confusion, he’ll claw his way to clarity by finding a joke. When my mom gave him back his wedding ring, which had to be removed when he was treated in the hospital for swelling due to congestive heart failure last weekend, he put it on, looked into her eyes, and said, “I do.”

It was another sweet moment in their 72-year marriage, a number my mother proudly managed to work into the conversation with all the “walk-ons” of the past week: the doctors, the nurses, the hospice intake workers… I think she would have even told the insurance people, if she hadn’t asked me to make the phone call for her.

I could write about more about my father and about my own struggles with sad moments, of which there have been far too many this week–in my own life, and in what’s happening to our country, and I’m sure I will in weeks to come. But what I really wanted to write about in this post was the idea of “walk-ons” in writing: how to use what could be considered extraneous details and incidents to our advantage.

One big difference between real life and writing, whether it’s fiction, non-fiction, or even poetry, is that anything one chooses to include in a piece of work needs to matter. Real life is full of irrelevant happenings like the man giving out the prayer books at the funeral, but readers don’t want the minutia unless the minutia means something. The objects, metaphors, place descriptions, and incidents we choose to include in our work need to create an layer of meaning that resonates, adding an extra glow. So, it’s helpful to ask ourselves when writing (regardless of whether it’s fact or fiction) what a particular image or set of details adds to a piece. Is it worth including, or does it simply bog down the pace?

Take the case of the man handing out the prayerbooks at the funeral home. If I describe a heavy man lumbering down the aisle under more prayerbooks than he can comfortably carry, I’m setting a different tone than if I’m describing a man with a nervous tick who grins at everyone as he hands them a prayer book and tells them to have a nice day. Either of these could add to the weight of a story or essay. But if I simply say, “a man handed us a prayerbook,” I’m wasting words with a flat sentence we don’t really need to hear.

Or, as in the case of my father, the point of a “walk-on” might be how one of your “characters” reacts to it–especially if your character is relatively quiet, the way my father is. Sometimes you can do a better job bringing people to life by emphasizing the smaller moments in a scene, rather than the larger ones. And showing people in action, rather than simply writing about them, is nearly always more effective in showing who they really are.

It’s those smaller moments I’ll remember about my father. As well as what they convey about the essence of his character: how he used humor to sidestep difficult emotions, and yes, like all of us deep-secret attention-seekers, he thrived on our laughter and appreciation of his jokes.

So I’m glad to have the memories, and glad for the opportunity to make scenes out of them, as I’m sure I will as the weeks and years unfold, letting the stories tell themselves and hopefully, through those stories, enabling him to live far longer than the time he has left.

A few days ago, after my rendez-vous with the tree I came across this quote from Jacoby Ballard, from a series of journal prompts I’ve subscribed to from Kripalu Yoga Center on the theme of Choosing Love.

A few days ago, after my rendez-vous with the tree I came across this quote from Jacoby Ballard, from a series of journal prompts I’ve subscribed to from Kripalu Yoga Center on the theme of Choosing Love. I’m personally very mixed on the “awards/contest” game for books because it seems like mostly a way of collecting a lot of exorbitant entry fees just to say your book won an award, but my publisher and I did submit to a couple of the more known ones. I was pleased to get a finalist designation (first runner up short-story and all category short-list) for the Eric Hoffer Awards, and a finalist designation in the short story category for the Independent Authors Network.

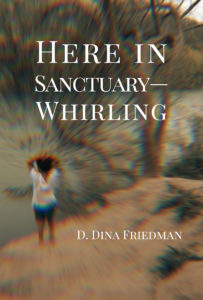

I’m personally very mixed on the “awards/contest” game for books because it seems like mostly a way of collecting a lot of exorbitant entry fees just to say your book won an award, but my publisher and I did submit to a couple of the more known ones. I was pleased to get a finalist designation (first runner up short-story and all category short-list) for the Eric Hoffer Awards, and a finalist designation in the short story category for the Independent Authors Network. It was a thrill to have my poetry book, Here in Sanctuary–Whirling, which drew heavily on my witnessing trips to the border and the children’s detention center in Homestead, FL, come out in early 2024. With the upcoming administration’s about to take over and put their extreme deportation plans in gear, this book feels even more relevant right now, and I’m continuing to look for ways to publicize it.

It was a thrill to have my poetry book, Here in Sanctuary–Whirling, which drew heavily on my witnessing trips to the border and the children’s detention center in Homestead, FL, come out in early 2024. With the upcoming administration’s about to take over and put their extreme deportation plans in gear, this book feels even more relevant right now, and I’m continuing to look for ways to publicize it.

Juliet might have said, a rose by any other name would smell as sweet, but in the writing world titles matter.

Juliet might have said, a rose by any other name would smell as sweet, but in the writing world titles matter.