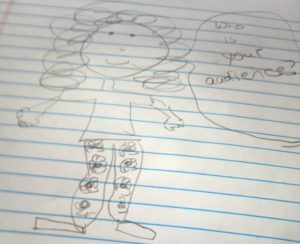

Back when I started teaching business communication and my children were still young, my daughter drew a cartoon picture of me: a frizzy-haired cartoon stick figure with my signature hippie flowered pants and a huge dialogue bubble coming out of my mouth that said, “Who is your audience?”

The picture, a light-hearted attempt at making fun of the teaching adventures and insights I talked about incessantly at the dinner table, lived on the refrigerator for a long time. I wish I still had it, but somewhere along the way, it joined the big compost pile in the sky.

More recently than that, I finally stopped teaching business communication, but the message lives on in my creative life. Every time I write something, I need to think, who is going to read this? Whom do I want to read this? My parents? My children? Other writers in my various circles of creative community? The general public? The literary public? The snotty branch of the literary public? My intimate friends who know and love me, but don’t really know me as a writer? Or is this something I’m writing only for myself that doesn’t really need a home in the wider universe?

Like many, I often feel driven to share my work because I want the affirmation–not so much to be told I’m a good writer, but to know that the reader got whatever important thing I was trying to express. That it mattered. That something I said moved them.

So it can be devastating when that doesn’t happen. Especially when a piece is brand new and I’m high from the excitement of having just birthed it. Later, as I gain perspective and see the piece as a work-in-progress that will likely continue to evolve, I feel more ready to hear whatever comments people might have, even if they didn’t get what I was trying to do (perhaps because I hadn’t really done it yet).

So, I tend to think about levels of audience when deciding to share a piece. The safest places–and pretty much the only places where I share raw work–are my various writing communities, because there’s a sense of all of us being in it together, and often the type of “allowable” comments are set in advance by the norms of the group. Therefore, I know I’m not going to get deluged with negative comments, irrelevant asides about how my experience is like theirs, or grammar corrections,

The least safe places, somewhat surprisingly, are in my close circle of family and friends– partly because their opinion matters too much, and I so desperately want them to grok what I’m saying. When they don’t, I feel crushed. It’s so hard to let go of the time my mother said, Can’t you write about anything other than death? Or when my husband, who usually gets it, reacted to a brand new, raw heavy heartfelt dump by telling me there was a comma missing in the second sentence.

And then there’s the bigger question of when to offer your work to an outside audience, which can set you up for tons of rejection, putting you at risk at denting the foundation of your inner confidence. And even if you’re lucky enough to get something accepted and published, you can end up as fodder for trolls on social media sites or critics who might give your work bad reviews.

If you take this scary plunge into the depths of different on audiences, on whatever level, affirm yourself for being brave. Here’s my brave attempt at recreating that picture from the refrigerator.  It’s a good reminder to think about our goals for writing and our reasons for sharing with others.

It’s a good reminder to think about our goals for writing and our reasons for sharing with others.

To subscribe sign up at ddinafriedman.substack.com

It’s one of the stories in my forthcoming collection, Immigrants (Creators Press, Fall 2023).

It’s one of the stories in my forthcoming collection, Immigrants (Creators Press, Fall 2023).

As the night broke into the beginnings of a cloud-covered day, we watched a bus pull up. A man held up his shackled wrists to the window. We stood in front of the bus, holding up hearts, and for a moment, we held up “business as usual” as the bus came to standstill. We surrounded the bus, shouting “I love you,” to the shadowy faces in the windows. And “No están solos. Estamos con ustedes.” (You are not alone. We are with you.)

As the night broke into the beginnings of a cloud-covered day, we watched a bus pull up. A man held up his shackled wrists to the window. We stood in front of the bus, holding up hearts, and for a moment, we held up “business as usual” as the bus came to standstill. We surrounded the bus, shouting “I love you,” to the shadowy faces in the windows. And “No están solos. Estamos con ustedes.” (You are not alone. We are with you.)  Then, the police came and since we had not planned for a civil disobedience action that would end in arrest, we let the bus pass through the gate to the plane. They parked a truck in front of the stairway, so we couldn’t see the people limping with their shackles up the stairs into the plane’s belly, but that image, along with other accounts of abuse, has been captured in

Then, the police came and since we had not planned for a civil disobedience action that would end in arrest, we let the bus pass through the gate to the plane. They parked a truck in front of the stairway, so we couldn’t see the people limping with their shackles up the stairs into the plane’s belly, but that image, along with other accounts of abuse, has been captured in

Two days into my South Africa trip, I started getting cold symptoms. I tested for COVID and was relieved to be negative, so I went on a safari and for a walk with rifle-carrying naturalists in the wild bush, chalking up the fatigue I was feeling to two consecutive red eye flights followed by the eight hour bus ride to Kruger National Park.

Two days into my South Africa trip, I started getting cold symptoms. I tested for COVID and was relieved to be negative, so I went on a safari and for a walk with rifle-carrying naturalists in the wild bush, chalking up the fatigue I was feeling to two consecutive red eye flights followed by the eight hour bus ride to Kruger National Park.  A few days later, when we arrived in Cape Town, my husband was also coughing and sneezing. Our symptoms felt like a typical cold, but just to make sure, we both tested again. BINGO! For both of us, a flaming red line.

A few days later, when we arrived in Cape Town, my husband was also coughing and sneezing. Our symptoms felt like a typical cold, but just to make sure, we both tested again. BINGO! For both of us, a flaming red line. I’ll just have to be patient, put on my mask and be happy enough to sit on an uncrowded beach and watch the sunset.

I’ll just have to be patient, put on my mask and be happy enough to sit on an uncrowded beach and watch the sunset.