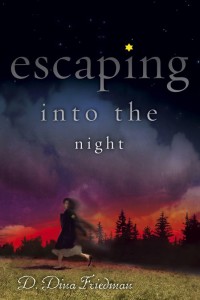

When I published my first book, Escaping Into the Night, with Simon & Schuster in 2006, I thought I had finally broken the publication barrier and was well on my way to achieving my goal of being a recognized author. Once that first book was published, the rest should be easy! And I had many ideas–and several manuscripts in various stages of completion in the drawer just waiting to be published.

But even though my contract required me to give Simon & Schuster an option on my next book before sending it anywhere else, they rejected my next manuscript. And the next. And the next. When I asked why, I was told that Escaping Into the Night didn’t do well enough–despite going into five additional printings and earning honorable mention designations from the American Library Association, Association of Jewish Libraries, and New York Public Library. When I reminded my editor of this, she said, “Well, you didn’t win a Newberry medal.”

O-kay… according to the Children’s Cooperative Book Center, approximately 5000 children’s books were published in 2006. Five of them won Newberry Honors. So, my book wasn’t in the top .001%. Gee! Sorry!

This is the thinking behind the predatory capitalist mentality and the “zero-sum game.” If you don’t win, you lose.

I’m thinking about this a lot this week while we’ve been in Florida managing yet another crisis with my father-in-law’s dementia. After being moved out of his home and into memory care a few weeks ago when his “sundowning” outbursts became too much for his home health aides to handle, he fell and broke his hip. In the last two weeks he has been in and out five different hospitals and rehab facilities. Each move has pressed further on his fragile ability to understand where he is and what is happening to him. At his worst, in another trip to the ER on Friday, he was shaking and crying and slapping at himself. I want to die! he screamed. You took it all away from me, and now I want to die. I’m already dead! I started dying when you took my apartment, my money, all my stuff!

As much as we patiently explained that his apartment was still there, and we could discuss whether he could go back to it after he was able to walk again (the apartment is inaccessible and he is completely bedridden at the moment), he could not be consoled. My father-in-law’s defining image of success–his only definition of success–revolved around independence: making his own decisions and doing things his own way. Once he lost that due to increasing dementia, in his mind, all was lost–a zero-sum game. He could not take a moment from his misery to appreciate even for one second some soothing music, a picture of his great-grandchild, the evocative shapes of the clouds on the skyline view out his hospital window, or us simply holding his hand and telling him that we loved him.

As I think about planning for my own aging, rather than focusing on the endless lists of financial minutiae that my father-in-law so meticulously put together and now lacks the cognitive ability to understand, I’m trying to instigate a practice now of cultivating gratitude for exactly the things I’ve been trying to point out to him that he does not see. This morning, in an attempt to “refill my empty tank” and fortify myself for another day fending off his anger on one end and negotiating intractable medical bureaucracy on the other, I spent a few minutes on the beach,  mesmerized at the purple hues of the sky reflected in the ocean, the sound of the waves, the gulls strutting around in the sand.

mesmerized at the purple hues of the sky reflected in the ocean, the sound of the waves, the gulls strutting around in the sand.  Hopefully, if I’m ever plagued by dementia, I’ll be able to pull up that inner reservoir of abandoning the zero-sum game and simply enjoy whatever the moment has to offer me.

Hopefully, if I’m ever plagued by dementia, I’ll be able to pull up that inner reservoir of abandoning the zero-sum game and simply enjoy whatever the moment has to offer me.

This is what I had to do as a writer 18 years ago: abandon the zero-sum game. And while it may not have been as difficult as that has been for my father-in-law (with admittedly less at stake, too) it still took a couple of years before I stopped thinking about being a writer as a win (big publisher)/lose (anything else) proposition and overcome the resulting depression that warped thinking caused.

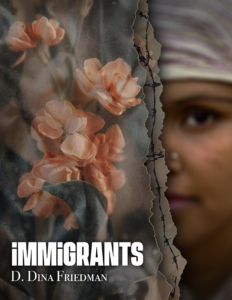

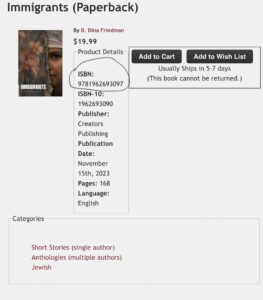

But in the last several years, I HAVE reclaimed myself as a writer. And broadened the definition of a writer as anyone who uses their words to express a truth they’re compelled to tell (even when that truth is embedded in a fictional story). And while all truths may not touch all people, and some people will be more skilled than others in telling their truths, it’s the sharing of truth-telling that matters more than how much recognition or accolades I (or someone else) might get. And on days when I might doubt my own convictions, all I need to do is remember the outpouring of love and support at my launch reading for Immigrants last week, as well as all the comments I’ve received over the years from friends, colleagues and even strangers who have told me that my writing touched them.

And incidentally, the very small publisher who published Immigrants also requested an exclusive option on another work of fiction and subsequently rejected it–before Immigrants was even published. LOL it never ends!

and that didn’t happen until six weeks after the book was published. In the meantime, I was grateful to the bookstores who were willing to take copies of

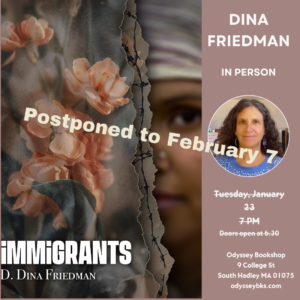

and that didn’t happen until six weeks after the book was published. In the meantime, I was grateful to the bookstores who were willing to take copies of  While I’m an admitted snowphobe when it comes to driving, I knew I’d likely be able to make it to the bookstore, which is only 5 minutes away from my house. But I also knew that others who were planning to come were driving much longer distances. I didn’t want to ask people to risk their safety. And I didn’t want to risk a low turnout. Even though I’d already bought the snacks and the ingredients for brownie-making, I decided it would be best to postpone.

While I’m an admitted snowphobe when it comes to driving, I knew I’d likely be able to make it to the bookstore, which is only 5 minutes away from my house. But I also knew that others who were planning to come were driving much longer distances. I didn’t want to ask people to risk their safety. And I didn’t want to risk a low turnout. Even though I’d already bought the snacks and the ingredients for brownie-making, I decided it would be best to postpone.

And as I was going full-steam ahead, a surprise snuck up on me. My poetry book Here in Sanctuary–Whirling was suddenly in its final stages of pre-publication. In fact, it’s scheduled to come out from

And as I was going full-steam ahead, a surprise snuck up on me. My poetry book Here in Sanctuary–Whirling was suddenly in its final stages of pre-publication. In fact, it’s scheduled to come out from  While I did what I knew I was supposed to do as a good book marketer: posting the link widely on social media and sending it around by email, there was a part of myself that just wanted to crawl into a dark place and hide from the rushing current of accolades. Can’t I just be humble? that small inner part of me whined. Why do I have to call so much attention to myself?

While I did what I knew I was supposed to do as a good book marketer: posting the link widely on social media and sending it around by email, there was a part of myself that just wanted to crawl into a dark place and hide from the rushing current of accolades. Can’t I just be humble? that small inner part of me whined. Why do I have to call so much attention to myself?