My 2.9 year old grandson, Manu, loves the playground, especially when there are no other children and he has the whole place to himself. A few days ago when we arrived, we saw another kid in the sandbox who waved to him enthusiastically. “That kid wants to play with you,” I said.

He hesitated before answering, then said, “I don’t play.”

Photo by Shel Horowitz

This surprised me because I have clear memories of being 2 and wanting nothing more than for other kids to play with me. I remember Linda, who lived a few houses down in the apartment complex we lived in and how I liked nothing better than running down the hill with her at top speed in our shared yard. And in kindergarten, I remember Mary Ann, with her perfect blond braids, how I cried because the teacher wouldn’t let me sit next to her.

While I don’t remember the specific incident, I also remember the day I came home from kindergarten crying because some kids had said or done something mean to me. My mother simply shrugged and said, “Children are cruel.”

I was shocked! Children? My tribe? (I was already aware of divisions: that I was a child in a land of adults and a girl in a culture where boys ruled.) But how could children as an entity be labeled as cruel? I was a child and I wasn’t cruel. And why was being cruel something to be shrugged about and accepted as a fact of life?

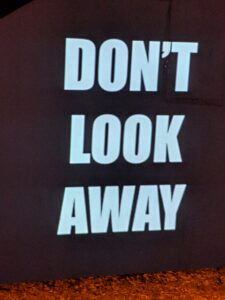

Unfortunately, cruelty is not something confined to children. Our human history of wars, torture, and the oppression of one group by another is all the proof we need. And if we want to fast forward to the present and our own country, all we need to do is look at the initial reports from “Alligator Alcatraz” (aka “Alligator Auschwitz”) where inmates are reporting no bathing facilities, one maggot-infested meal per day, elephant-sized mosquitoes, 24-hour lights, and alternating periods of sweltering heat and chilling cold.

What should we do? Shrug, and say, “People are cruel?”

In both my most hopeful and most devastated days, I find myself pondering why we humans as a species are the way we are. How can we possibly have the capacity to harm each other in the ways we do? The “hopeful me” looks at this question as a puzzle that, once solved, can change the entire trajectory of how humans can live together on the planet, while the “devastated me” wants to curl up somewhere and cry–with many more tears than I ever shed because I couldn’t sit next to Mary Ann.

Elon Musk recently said, “the fundamental weakness of western civilization is empathy.” But that’s the voice of the dark side. Empathy is the only thing that might be able to save us from ourselves. It’s empathy for others that can catalyze those of us who have the privilege and the capacity to speak out. And we must speak out–despite empathy’s ability to also render us paralyzed because we feel the pain of others so deeply.

On a recent day at the playground, Manu wanted to climb on a rock where another little boy was standing. He stayed at the bottom of the rock for minutes looking up at the boy, who stared down at him from the top, neither of them saying anything, just staring each other down and holding their position. Finally the boy on the rock made a fist and released his index finger, as if he were shooting a fake gun. It was subtle gesture, and I wasn’t sure if I was interpreting it correctly, but I think I was, because he did it several more times.

Where did he learn that? I wondered, with horrified distaste. Who taught him?

Then I tried to use my empathy, and reason from the kid’s perspective. He was enjoying being on the rock and didn’t want anyone encroaching on his space. We humans have an innate tendency to protect what is ours, and when we’re young we often have to learn not to grab or be aggressive towards others to get what we want.

Even though neither of the little boys thought so, there was enough room on the rock for both of them. Just as there’s enough room in our country for all of us who are here to live peacefully with each other.

Eventually, the boy’s mother finally came over and picked him up, enabling Manu to climb on the rock unimpeded. Eventually, Manu, too, will need to learn how to share his space. Hopefully he’ll get to a point where he thinks it’s much more fun when other kids are also at the playground. Hopefully, we’ll also get to that point. Somehow. Some way.

Subscribe at https://www.ddinafriedman.com

–and struck by the sensitivity, depth and humor in the brief excerpt he read from this one. Most of all, I was moved by his thoughts on what it means to be a writer–what it means to be a human, actually–in these troubling times.

–and struck by the sensitivity, depth and humor in the brief excerpt he read from this one. Most of all, I was moved by his thoughts on what it means to be a writer–what it means to be a human, actually–in these troubling times.

When I went to the border in 2020 I heard many stories of bravery, all of them spiced with horrific moments that made me flinch, or cry, or both: kidnappings, gang break-ins, death threats to their children, rapes…One man told me about being forced into a car with his 8-year-old daughter by kidnappers after spending weeks in the hielera (Spanish word for ice box where they keep detainees). With his permission, I chronicled his story into a poem (pasted at the end of this blog) which was first published in my book,

When I went to the border in 2020 I heard many stories of bravery, all of them spiced with horrific moments that made me flinch, or cry, or both: kidnappings, gang break-ins, death threats to their children, rapes…One man told me about being forced into a car with his 8-year-old daughter by kidnappers after spending weeks in the hielera (Spanish word for ice box where they keep detainees). With his permission, I chronicled his story into a poem (pasted at the end of this blog) which was first published in my book,  Holding this man’s story and the stories of others was devastating. I came back from that trip feeling smothered under the weight of such sadness, confused about how I could continue going blithely about my days feeling grateful for the trees, and my friends, and the small sweet details of my privileged life.

Holding this man’s story and the stories of others was devastating. I came back from that trip feeling smothered under the weight of such sadness, confused about how I could continue going blithely about my days feeling grateful for the trees, and my friends, and the small sweet details of my privileged life.

We also went to buy flowers for the yard–four generations of us: me, my mom, my daughter and son-in-law, and my 2-year-old grandchild. As we meandered through the aisles of colorful blooms, and then loaded them all into my daughter’s station wagon, I thought, this is what we need to do. Somehow, we need to keep things growing. Even if my mother’s yard is small and gated like all the other yards on the block, there’s hope in those flowers. And kindness in sharing their beauty with the people walking by, both those she knows and those she doesn’t.

We also went to buy flowers for the yard–four generations of us: me, my mom, my daughter and son-in-law, and my 2-year-old grandchild. As we meandered through the aisles of colorful blooms, and then loaded them all into my daughter’s station wagon, I thought, this is what we need to do. Somehow, we need to keep things growing. Even if my mother’s yard is small and gated like all the other yards on the block, there’s hope in those flowers. And kindness in sharing their beauty with the people walking by, both those she knows and those she doesn’t.