Yesterday, I found myself meandering through my short story file and opening up some titles of work I didn’t recognize to see what they were.

Sometimes when I do this with an archival file of past writing, I find some pieces with hidden sparkle that I’m inspired to work on. But yesterday, several files that I uncovered brought me nothing but embarrassment and a slight tinge of shame. The situations I’d tried to fictionalize were too close to autobiographical for comfort, revealing truths I might have needed to process at the time, but likely did not have enough relevance or context to be useful, insightful, or enjoyable to outside readers.

And since I’m a big “what-if” fantasizer, I couldn’t help but worry about what might happen if somehow, after I was dead, these thinly disguised files were seen by the people involved. I didn’t want to risk being hurtful, especially with no way to explain, apologize, or make amends.

So I did a radical thing. Command A, Command C, Delete. Move to trash.

https://freebie.photography/concept/slides/throw_away_concept.htm

Four key strokes. The words were gone, the files disappeared.

And then I worried. Had I been too rash in throwing away my work? Was there something salvageable in these pages I could use later? Was the impetus to toss generated by my (somewhat) objective writer-self, or my condemning inner critic, who probably thinks I should throw away everything?

Too late! They were gone.

And while I’m obviously having second thoughts, I do think it was the right decision, mostly because of the hurtful potential of these particular half-drafted stories. But also because they were all so old, I barely remembered them. And because I really was no longer drawn to write about these things. And if I am in the future, I think the stories will be better served starting afresh with whatever wisdom, perspective, and distance I’ve gained between then and now, enabling me to crystallize the issue and contextualize it in a way where the specific situation and actual cast of characters are no longer recognizable.

When you toss something right away, it’s usually because your inner critic is telling you it’s crap, and we all know how unreliable inner critics can be. So I wouldn’t recommend throwing away anything you’ve written in the last year–or maybe in the last five years, especially with the luxury of fairly unlimited electronic storage. But anything older than that–the choice is yours. Is there anything left in the piece that draws you? And if not, do you want this work to be part of whatever legacy you might want to leave?

So now I’m contemplating what else I should toss. A few months ago, a close friend from high school gave me a whole bunch of letters I’d written to her from the ages of 17 to 23. I read through them all and cringed, even if I could have had more compassion for that young, naive, and giddy girl, who comes off as so darn shallow. My first impulse was to build a fire and ritually burn them, as if putting them in the recycle box wouldn’t be good enough. But instead I buried them under a pile on my desk. A month later, I took more time when I re-read them, and was able to be a little more forgiving of my younger self’s flaws, but I’m still inclined to get rid of them soon–along with most of the contents in the boxes of journals in the attic, and the manila envelopes filled with letters friends wrote to me during my teenage years.

And at some point, I intend to go through more of my old writing and figure out what I want to keep, and what really doesn’t need to be anywhere in the universe, especially with my name on it.

Is it Swedish death cleaning, or more carefully constructing the legacy I want to leave? Perhaps a little of both. And yes, I admit to intentionally wanting to curate a picture of my better self, which may not be the whole truth. But how different is that, really, from waking up each day and trying to be that better self in real life?

Subscribe at https://ddinafriedman.substack.com

At about 5:30 pm on Saturday, just as I was getting into my car after a hike that featured a visit to my favorite “best friend” beech tree I checked my phone. There was the rejection–a form one I’d received several times before, kind, as always, reminding submitters of the number of poems received and encouraging people to try again.

At about 5:30 pm on Saturday, just as I was getting into my car after a hike that featured a visit to my favorite “best friend” beech tree I checked my phone. There was the rejection–a form one I’d received several times before, kind, as always, reminding submitters of the number of poems received and encouraging people to try again.

Notable was the number of paintings by Cezanne and Renoir. There were at least one or two, if not more, works by these artists in every room. In fact, there were so many paintings by Renoir, I found myself wondering how he ever had time to create all of these in addition to the many I’d seen at other museums in the world.

Notable was the number of paintings by Cezanne and Renoir. There were at least one or two, if not more, works by these artists in every room. In fact, there were so many paintings by Renoir, I found myself wondering how he ever had time to create all of these in addition to the many I’d seen at other museums in the world.

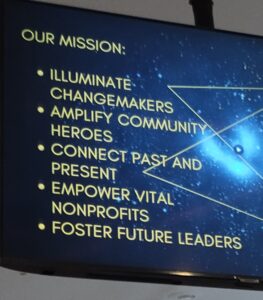

Later that evening, I was invited by an old friend to attend a different arts-oriented event celebrating the city’s community leaders. This was organized and sponsored by

Later that evening, I was invited by an old friend to attend a different arts-oriented event celebrating the city’s community leaders. This was organized and sponsored by