I’ve noticed over the years that I get far more likes on social media for my personal posts than my political posts. Especially if the personal post is a happy one. It makes sense. On the whole, people would rather read something uplifting, poignant, or inspirational than the gloom and doom embedded in political messages, even when they convey what I think is important information or ask people to engage in a quick, painless action.

Because of this observation, I’ve generally been judicious about posting political content, even in these trying times. But lately I haven’t been able to help myself when nearly every day I come across another story of someone being wrongfully taken by ICE and sent to prison: sometimes here in the U.S. (although often thousands of miles away from their families), and sometimes to El Salvador, where the U.S. no longer has jurisdiction over their cases and torture and abuse are even more rampant.

In many of these cases, the people taken have no criminal record. In fact, they often have legal status: a green card, a visa, an asylum case pending. In nearly all of the El Salvador deportations, the people detained have been denied the opportunity to speak to an attorney or argue the charges against them in court. Instead they are quickly loaded, shackled onto a plane simply because someone has accused them (often based on a tattoo or hearsay evidence) of being a member of a gang.

In many cases, when ICE cannot find the person they are looking for, they make collateral arrests of whoever happens to be nearby. Sometimes these people are U.S. citizens, who are eventually released, but not until they’ve dealt with the trauma of spending several nights in jail. And those who aren’t citizens–hard-working people with no criminal record–enter the detention/deportation system, even if they have parole or asylum claims pending.

Even tourists have been arrested, strip-searched and sent to jail for visa mix-ups or under suspicion of plans to work illegally.

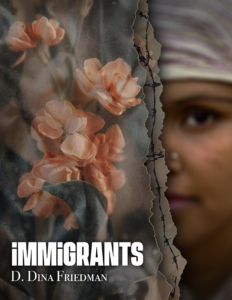

During this administration’s first term, when I wrote the stories in my collection Immigrants, I tried to envision the impact of DT’s policies on real people. While there were love stories that ended with deportation, a woman facing a dilemma of whether or not to bail out her housekeeper’s brother, and a mother in a squalid border encampment who sent her daughter over the bridge to the U.S. alone, there was a still a softness to the stories. I did not talk about the torture and abuse inherent in detention facilities. I balanced these stories with others where immigrants played a positive and vital role in people’s everyday lives. And I took the stance that these people were victims in a system that had gone out of control due to misguided information and decision-making.

During this administration’s first term, when I wrote the stories in my collection Immigrants, I tried to envision the impact of DT’s policies on real people. While there were love stories that ended with deportation, a woman facing a dilemma of whether or not to bail out her housekeeper’s brother, and a mother in a squalid border encampment who sent her daughter over the bridge to the U.S. alone, there was a still a softness to the stories. I did not talk about the torture and abuse inherent in detention facilities. I balanced these stories with others where immigrants played a positive and vital role in people’s everyday lives. And I took the stance that these people were victims in a system that had gone out of control due to misguided information and decision-making.

But in current times, these people are no longer victims; they’re prey. Deliberately hunted. Shredded. Devoured. And they don’t just include people who entered the U.S. without documentation. They’re people with legal status who are being imprisoned for writing op-eds or social media posts against the government’s point of view, or for organizing peaceful protests. Or they’re people who just happen to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

I don’t feel like I can write any stories about immigrants any more because the true stories are too hard to read. And to write anything that waters down the truth is mitigating the effects of what is happening.

Yet, I know that as a writer, I have a responsibility to speak out.

So, on my Facebook feed, I’m posting these stories as I come across them. Most are from Witness at the Border, a group I worked with when I went to the children’s detention center in Homestead Florida in 2019 and the Brownsville/Matamoros border in 2020. You can read quick summaries of some of these cases in this Axios article, but it’s the power of detail in the actual stories that really strikes a chord. In my fiction collection, one of my goals was to change people’s hearts and minds by inviting them to really know the characters I wrote about. The stories profiled by Witness at the Border do just that. I’m hoping we can get past the sadness and disempowerment and channel the power of these stories as inspiration to take whatever actions we can to make this stop.

Subscribe at https://ddinafriedman.substack.com

And one thrill from this past AWP was to meet two of these people for the first time: Sage and Carla in real life.

And one thrill from this past AWP was to meet two of these people for the first time: Sage and Carla in real life.