When I was a child in New York City, I was one of the few kids who wasn’t an immigrant or a child of immigrants. I remember being awed when I’d visit my friends in their homes and listen to them speaking animatedly in another language–Spanish, or Chinese, or Greek–before switching back to me and talking in just as fluent English. I felt envious and ripped off that my family couldn’t speak any other languages.

In elementary school, nearly every year our teacher would give us a homework assignment to describe the country we, or our parents, or grandparents had come from, and then present that to the class so everyone could learn about it. “You come from many different countries,” my parents would tell me, as they ticked off the different areas on the map that my great grandparents (and sometimes great-great grandparents) had lived before sailing to Ellis Island: Lithuania, Germany, Holland, Russia, the Ukraine, Poland…

This was an odd assignment for me because I felt no connection to any of these places. We had no legacy of language. My parents didn’t know Yiddish. Even my grandparents–all of whom were born here–knew very little. I felt so American, so boring, and sad that I had absolutely nothing for “Show and Tell”

But the point isn’t to complain about my experience as much to reflect back on an instance when being an immigrant was celebrated. And I did not go to a “lefty commie school.” This was a regular public school in New York City where we pledged allegiance to the flag every morning, and learned about how “great” America was. And part of what made it “great,” we learned, was immigrants. New York was a “melting pot.”

I currently prefer the term salad bowl, a metaphor that allows us to acknowledge everyone’s individual culture rather than envisioning us all melting into some unidentifiable assimilated conglomeration. However, neither image does the kind of harm as the recent outrageous lies about immigrants in Springfield, Ohio, and the overall vilification of immigrants put out by MAGA Republicans–who are calling for a large-scale deportation of not only undocumented residents, but also those who have obtained a legal path to be in this country.

Had this been carried out when I was a kid, it would have included nearly everyone in my class.

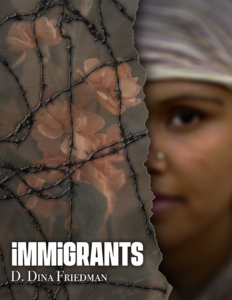

When I wrote my collection of short stories, I wanted to emphasize how immigrants are everywhere, just as they were everywhere in my childhood. Some of my stories are overtly political, drawing on my experiences as an activist, but most of them aren’t. They’re simply tapestries woven with real people–some of whom simply weren’t born in the U.S. I write about humans in situations with issues. That’s what’s always grabbed me in fiction–the ways we struggle to love the world, each other, and ourselves.

When I wrote my collection of short stories, I wanted to emphasize how immigrants are everywhere, just as they were everywhere in my childhood. Some of my stories are overtly political, drawing on my experiences as an activist, but most of them aren’t. They’re simply tapestries woven with real people–some of whom simply weren’t born in the U.S. I write about humans in situations with issues. That’s what’s always grabbed me in fiction–the ways we struggle to love the world, each other, and ourselves.

So I guess that’s my “show-and-tell”–only 50 years late. Hoping we can get a little of that immigrant love back. All of us belong in the salad.