I’m writing this post in collaboration with Tzivia Gover. Tzivia and I have been orbiting in similar circles for decades, and we’re both regulars at the same drop-in writing group in our community. We recently got excited about a question raised by another writer in our group. “People keep telling me to put together a book. But that would be so much work. I’m retired. I want to enjoy writing, not commit myself to a long slog.” This got us thinking about how to balance the joys of writing with the inevitable oys —the difficulties and discontents. So we decided to carry the conversation into our Substack newsletters. As you will find, having a writing community is one of the joys in each of our writing lives! We invite you to read each of our reflections—and join the conversation in the comments.

Dina …

Even though I’m often jazzed by the editing and revision process that’s needed for long, extensive projects, I’m also a survivor of several slogs–which had many, many moments of NOT FUN. So I immediately understood this far too familiar dilemma raised by our fellow writer.

“To keep going you’ve got to find the joy in the process,” I told him.

Sometimes, that joy can be envisioning the overall outcome and holding onto that vision. Sometimes it can be the pleasure of revising a single poem, or paragraph, or scene. For me that often involves focusing on paring down words I don’t need or substituting words and phrases with more heft and resonance and sound quality. I find it fun to look at the before and after and see how far I’ve come at chipping away at a block of marble to make it beautiful.

The hardest part for me–the “oy”–is when I have to conjure up details about a character/scene, etc., that I haven’t been able to conceptualize, or to clarify something that makes perfect sense to me but others don’t get. In my mind, I often compare this process to giving birth. “Push, push, push,” I literally say out loud to myself. No, it isn’t fun–but that’s when it’s time to go back to the vision and trust that somehow, I’ll get there.

It just won’t be quick. And that’s ok. Patience is a virtue—not one I have a lot of, but one that’s good to cultivate. Besides, while I’m going through these slogs, I can still get some instant gratification by writing short generative pieces that give me the creative rush I’m constantly seeking.

Tzivia …

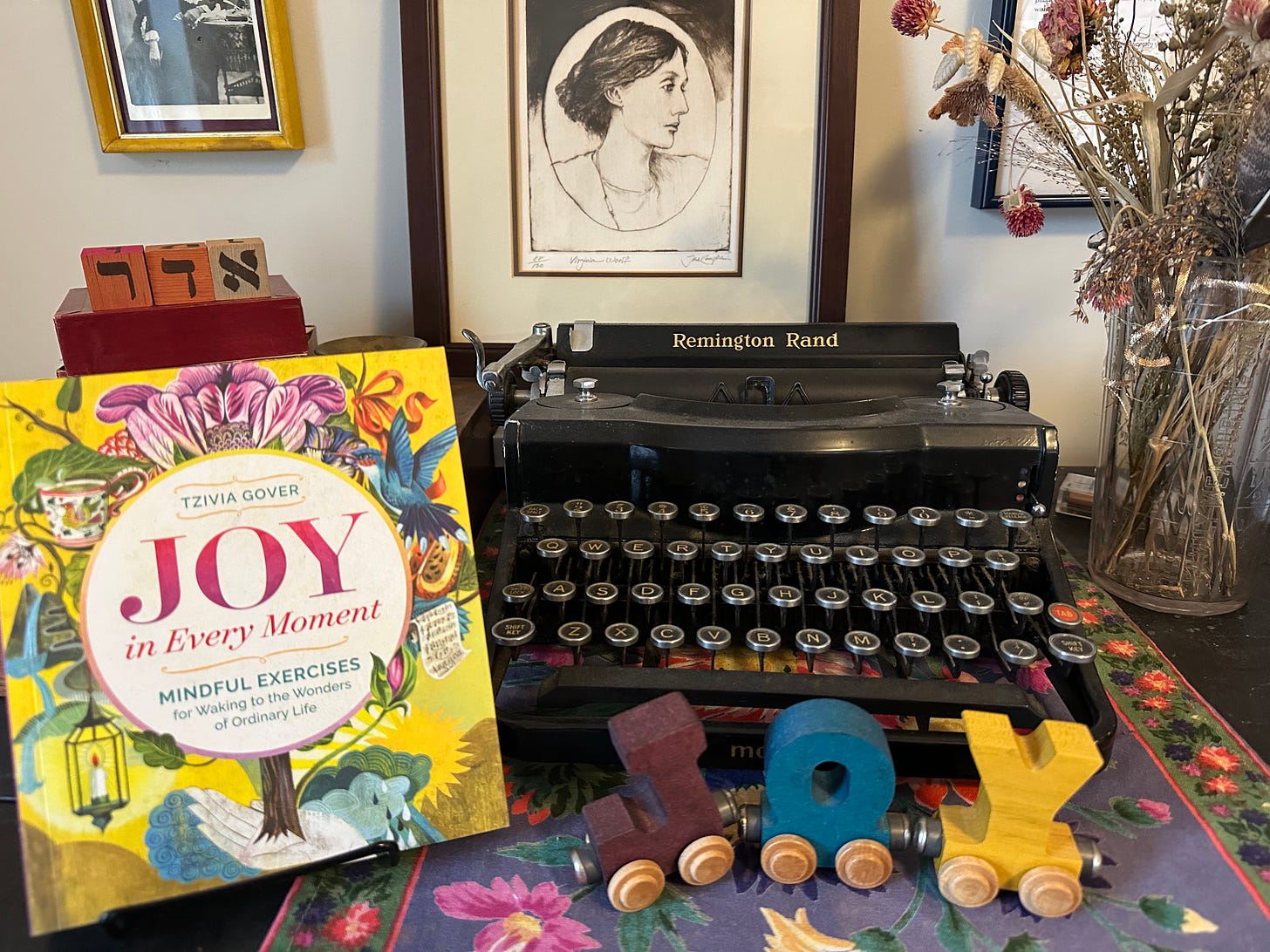

Some years back, while writing my book, Joy in Every Moment, an inspirational self-help book about accessing more everyday happiness, I was scrambling to make my deadline and tapping out sentences through gritted teeth. The time pressure, the critical voices chiding me, and the overwhelm of everything else that was on my plate at the moment were crowding in on me

Photo by Tzivia Gover

I promised myself I wouldn’t make writing a book about joy into a dreary job. To remind myself of my intention I placed a string of children’s wooden alphabet letters on my desk spelling out: J-O-Y. Each day when I sat down to write, that word smiled back at me, reminding me why I was there.

But writing with joy doesn’t mean that I’m going to love every minute of it. Daily writing is tiring. The transition from illuminating idea to words on the page can feel like mud-footed disappointment. Tedium and slog are part of the territory each writer must traverse. But with experience we learn that the effort is rewarded in the form of the well-earned satisfaction of having a reader sigh at the end of your poem, or seeing your work in print and knowing that you’ve said what you wanted to say, and you’ve said it as well as you can.

Meanwhile, I look for joy where I can find it.

Let me wax poetic about rooting into word origins, revising a sentence until each word slips, as if slotted, into just the right place, and of unraveling a knot of paragraphs to find the order that makes an essay sing.

And when the going gets hard, connections with other writers who understand the oy and the joy of the craft sustains me through storms of self-doubt and eases me around the rocky edges of despair when it seems nothing is coming together on the page.

Add to that the act of collaborating with other writers (as Dina and I are doing now) and the joys multiply.

Where are you finding the oys – and joys – in your writing life today? Drop a comment below.

Check out Tzivia’s Substack Newsletter—This Dream is A Poem here.

To subscribe to this blog, visit ddinafriedman.substack.com