My father died a week ago, in the early hours of Saturday morning March 1, 2025–in his sleep, in his own bed, at the age of 93 with his wife of 72 years sleeping by his side. While he’d been failing in recent weeks and on hospice, the quickness still came as a surprise, but I’m enormously grateful his death was peaceful and pain-free.

Last week, I wrote about being in a still space, unable to grasp the words that captured the profound sadness I was feeling about my father’s imminent death. While I remain in that foggy place, punctuated by a few rushes of angry winds and smatterings of quiet rainy weeping, I’ve managed to unearth a few more words about my father and his impact on my life.

As a child, my father played stickball on the streets of the Bronx. He was “the extra man,” which meant that when the other players were chosen, the team captains would once-twice-three shoot for the extra man. And then, whoever won would say to the captain, That’s okay. You can have him. Then they’d send him off to right field, which he had to share with Harry Jupiter. My brothers were lucky to inherit my mother’s athletic ability, but I spent my childhood being picked last on every time in school and day camp, and when I stood at the volleyball net, the team captain made sure to tell me not to even try to hit the ball if it came toward me. Someone else would cover. When I complained to my parents about this shame and humiliation, my father would once again tell me, what I came to think of as the “Harry Jupiter story.” (Underlying message: it’s your genetic fate; there’s nothing you can do about it).

But while I’ve often lamented inheriting my father’s unathletic genes, since his death, I began to wonder if being out there in right field, where there wasn’t too much going on, or being on the bench while Harry Jupiter took his turn, enhanced one of my favorite qualities about my father–a way of stepping outside the face value of the moment and taking a sidelong, irreverent view of the world, which seemed to be the genesis of the ironic and witty one-liners he was known for. I’ve never been a one-line comic, but like my father, I’ve always been a daydreamer. By example, he taught me that it was perfectly okay to take respite in the fog of my own mind and develop my own ways of expressing whatever I perceived.

My father also modeled another way in to the realm of the imagination, which was through playfulness. When I was a kid, all the inanimate objects in the house had their own personalities. Every day at breakfast, my father would flap the tea kettle’s steamy spigot open and shut, and let it utter its croaky greeting, daily kvetch, or philosophical witticism. And bath time was an adventure with Sammy the Soap and Tommy the Towel, characters that my children and nephews grew to love, and which I’ve tried to resurrect with my grandchild. By example, my father taught me that when playing with characters we could be as ridiculous and uncensored as we wanted to be. And this may have been why it felt so easy and normal to have imaginary friends as a kid, when I didn’t have too many real ones. All this childhood practice also made it easier when I started writing fiction. I could just close my eyes, dive in, and imagine my characters’ voices.

I believe this trait of embracing the unbridled mind, whether through play or daydreams, with a no-holds barred first-draft permission to probe the world of the subconscious without editing or self-censorship, is an absolute necessity to becoming a writer, and far more important than any genetic predisposition or so-called talent. But since I came from a family that emphasized the limitations of my genetic inheritance early on, I’m glad that writing was in our family’s genes. I fell asleep every night to the sound of my father’s manual typewriter clacking away at scripts for the documentaries he wrote and produced for WWOR TV.

In sharing stories with my family this past week, one of the key things that stood out was my father’s humility. My nephew, for example, who knew his grandfather only in his retirement years, was unaware until quite recently that my father had received several Emmy nominations and two awards for his documentary work. My father just wasn’t the type to mention it. Somehow this makes me feel validated for choices I’ve made to focus on my writing, rather than hyping my work, my brand, all that sh*t. Even in blogging, which is about the one marketing-related thing I regularly do, I’ve made the choice to keep it personal and hopefully focused on insights that can help others, as my father did. The people I spoke to this week who worked with him told me he always encouraged their ideas and inspired them to take leadership.

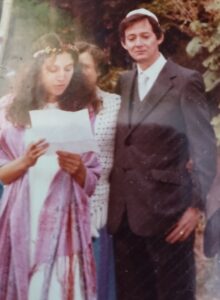

Dad and me at my wedding (Mom in background) October 1983. Photo by Brian Goldman.

So whether it’s genetic or not, thanks, Dad, for showing me the path forward to writing, playing, and dreaming.

Subscribe at https://ddinafriedman.substack.com